Critical and Creative Thinking

The current obsession with teaching basic skills continues to take centre stage with politicians and media commentators on education. This focus is reflected in the curriculum students are presented in the classroom. The latest research into the workings of the brain, exposes the damage that comes with this approach. It is obvious that by reducing the curriculum there is a reduction of the creative power of a child’s working memory and consequent decline in their ability to think critically. Instead of reducing the content of our curriculum the more diverse our lessons are and the more varied our delivery of those lessons the better equipped our students will be to succeed in these complex times.

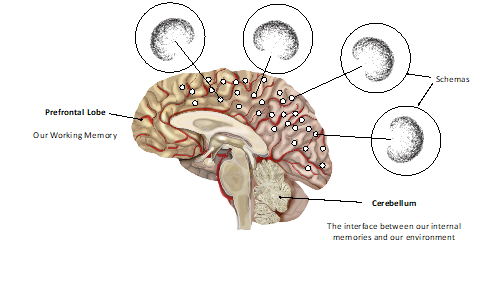

The brain is complex, perhaps the most complicated object in the universe and for years we have tried to understand how it works. How do we think, act, feel – if it is not the brain than what is it that drives these experiences? This essay aims to move this quest a bit further along the road introducing the idea that the cerebellum may is becoming recognised as the engine room of all cognitive processes.

The cerebellum is often referred to as the ‘little brain’ in fact its name comes from the Latin for that same description. The title was really obvious as it looks like the whole brain with two hemispheres that sit each side of a central line. This structure sits on top of the brain stem and behind the mid brain. The cerebellum takes only 10% of the brain’s volume but it contains half the brain’s neurons.

Early observations made the link between the cerebellum and a person’s motor skills and balance. Like all early neurological studies on behaviour, conclusions about the purpose of brain regions were inferred by the loss of functions after there was an injury to a specific part of the brain. As far as the cerebellum is concerned, assaults on it resulted in changes to the motor functions and/or balance of the individual and for years this was considered its total function to ensure stability in space. This drive to reconcile the balance of the body relative to the outer environment has been referred to as the cerebellum constant.

More and more the cerebellum is becoming recognised as the controlling mechanism of all behaviour. It has two modes of management, the first is to hold the model of how things should be; based on the individual’s history both genetic and environmental. The second is to scrutinise incoming stimulation from the internal and external situations against the expected conditions. If there is a match nothing happens however, when there is a mismatch the cerebellum initiates a ‘behaviour’ that has in the past worked best to return to the balance between the anticipated and observed stimulus.

This anticipatory system is automatic, that is the response to the misalliance between observed and expected conditions is a feed- forward process, it is immediate; there is no conscious or unconscious evaluation of the situation prior to making a response. This is easy to comprehend when thinking about balance or motor skills but the feed-forward characteristic of the cerebellum’s action has profound implications when thinking about children whose behaviour we want to change. At the time of exposure to a stressful situation when there is an imbalance in the cerebellum, the child has no choice about how they react, the feed forward characteristic of this process determines their action.

Although, from my studies there is no articulated description of how the outcome of any adjustment made during an ‘event’ leads to a change in the cerebellum’s anticipation when those same set of conditions re-occur; however, there must be a change because we can and do change our behaviour in response to situations over time. The strong links across the whole brain from the cerebellum, particularly to the cerebrum where memories are located compels the conclusion that it is the change of memories that inform the re-set of the cerebellum after any event.

The illustration below describes the process the cerebellum goes through in any situation. We perceive any conditions through our receptors and when confronted the cerebellum compares the circumstances we perceive with that which we expected. If there is a clash the cerebellum immediately feeds forward an action. This is automatic and not based on any ‘reasoning’ at the time the event occurs. The mind evaluates what happened after the action and creates memories that are fed back into the cerebellum to modify the expectation. The strength of this process is the same as any memory formation. It is relative to the emotional level and/or the consistency of the action - consequence connection.

This instant response has always been attributed to the amygdala however, I contend that the ‘feed-forward’ process is directed at the amygdala which in turn produces the fight/flight/ freeze reaction we observe in times of extreme stress.

The brain’s only power is to initiate movement through the excitation of an electro/chemical action. When dealing with actual body movement this has a well-known connection with the cerebellum; messages are sent out to adjust our body in space. However, this ‘initiation’ also occurs for all the brain’s activities and although there may not be any physical movement it is the cerebellum that initiates the electro/chemical transmission to all parts of the brain resulting in the establishment of a physical event, and emotion or a memory. All of these allow for an examination of the situation away from the cerebellum.

I’m aware that this is a fairly complex explanation of the process but the real difficulty in understanding this most intricate organ is overwhelming. The message for educators is that in order to function a child has to build-up a bank of memories that can be contrasted to the incoming stimulus. Of these, the most significant is the memories of social interactions which is the philosophy behind our model of creating an educational environment. These social often emotional memories are laid down in a family context and when this is less than ‘ideal’ it becomes the school’s task to do this.

However, the undertaking of a school should not be to reconstruct a child’s bank of social memories but rather create a set of memories that allow the child to access when faced with more complex, cognitive challenges. Their success in doing this is directly linked to the abundance stored in the cerebral cortex. It is obvious, that if we want our students to become creative and critical in their life it is important that we expose them to as wide a variety of experiences and subsequent memories as we can.

Of course, numeracy and literacy are important but think about how many of the memories acquired in these lessons are accessed in later life when you think about how you, as an adult navigate your work and life. If schools are to prepare children to actively participate in and contribute to their community the more diverse the educational experiences we provide for them the more beneficial their contribution will be.